tags : Computer Memory, Garbage collection

Memory types for programs

Two broad types, Static and Dynamic. (Stack and Heap are Dynamic allocations)

Static

- The layout is known at compile time

- Early 1950s (Fortran)

- No runtime allocation

- Fixed Size and variables bound to initial memory locations

- No Recursion

Stack

- Was introduced to support recursive calls with ALGOL

- Grows downwards ⬇️

- Stack pointer and base pointer are manually worked on in Assembly

- Stack allocation is automatically managed in languages like C

Heap

- Any memory chunk can pass around

- We can consume memory when needed

- Grows upwards ⬆️

- 🐉 Issues: Dangling Pointers and Memory Leak, which can be solved by GC.

- Dangling Pointers: When a pointer is pointing to a memory location that’s been freed! (Free objects too early)

- Memory Leak: More memory on the heap than needed. A chunk is just there in the memory taking space and nothing is pointing to it. (Forget to free needed object)

- Usage: C:

mallocandfree, C++:newanddelete, Go:escape analysisandGC

Mechanisms for Memory Allocation

Free list

Maintains list like data structure of free blocks. There are several ways the search mechanism for free blocks can be done: FirstFit, NextFit, BestFit, Segregate Fit(probably the best so far)

- FirstFit

- First block that is large enough to satisfy the request is allocated.

- NextFit

- Search starts from the last block that was allocated

- Looks for the next block that is large enough to satisfy the request.

- BestFit

- The block that is closest in size to the requested size is allocated.

- Segregate Fit

- Free blocks are divided into several lists according to their sizes

- Search starts from the list of blocks that are closest in size to the requested size.

Buddy allocator

- Used for allocating larger memory blocks, typically greater than a page in size.

- The Linux kernel divides physical memory into power-of-two-sized blocks, and the buddy allocator allocates and deallocates memory in these blocks.

- The buddy allocator is used by several kernel subsystems, including the page cache and the buffer cache.

Slab allocator

- The main idea behind is that most of the time, programs, especially kernels and drivers, allocate objects of the same size.

- Used for allocating smaller memory objects, typically less than a page in size.

- It maintains caches of objects of a specific size, and when a new object is allocated, it is assigned from the corresponding cache.

- Used extensively in the Linux kernel for managing data structures and objects, such as file descriptors, inodes, and network sockets.

- There is no slab allocator in user space(linux). In kernel, slabs are used for fixed size allocation. Most data structures in kernel are power-of-2 sized structures(i.e fixed sizes).

- You can have a slab allocator in userspace but it would not probably make too much sense

- See Slab Allocator

Note about userspace allocation

mallocand its variants (jemalloc,tcmalloc,dmallocetc.) handle the memory allocations in user space.- They get a large chunk of process virtual address space from kernel using

mmap(....MAP_ANONYMOUS...)and manage the address space using internal data structures like RB-tree

Object Header

A data structure used to maintain the state of each object for the allocator/collector purpose. It can contain things like markbit, ref count, freeblock flag etc.

> On x86_32, W=4bytes, so 5 bytes of

malloc(5)needs 3 bytes of padding, the object header then will take another +N bytes on top of that. So were’re actually adding some overhead to whatever memory we request

Shared Memory Allocation (shm_open)

See Inter Process Communication

Memory Fragmentation

Internal

Waste of space by allocating more memory than what was requested by the user (which is what the buddy allocator does).

External

- When the free space does not contain large contiguous regions

- Even though the allocator might have plenty of free space, it cannot handle large allocation requests because it does not have adequately large free contiguous spaces.

- Extreme of external fragmentation is having the even bytes allocated and the odd bytes free. Although the allocator has half its space available, it can only allocate 1 byte regions.

- Maintaining a free list helps here

- Temeraire: Hugepage-Aware Allocator | tcmalloc

malloc

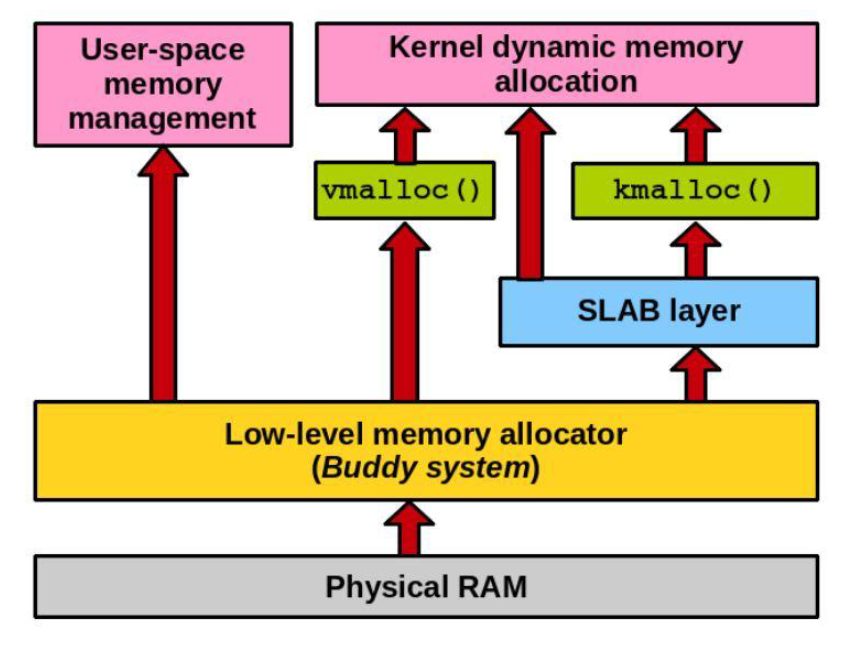

malloc, vmalloc, kmalloc

- kmalloc

- Used in the kernel, lives in the kernel

- kernel memory allocation

- Allocates memory from the kernel’s memory pool.

- Allocates physically contiguous memory, suitable for low-level operations.

- Can allocate less than a page size.

- vmalloc

- Used in the kernel(modules and device drivers), lives in the kernel

- virtual memory allocation

- Allocates memory that is not physically contiguous in RAM.

- Uses

pagingto map non-contiguous memory onto a contiguous VAS.

- malloc

- Used in user space

Writing a malloc

- Malloc tutorial

- CS170: Lab 0 - MyMalloc()

- Memory Allocators 101 - Write a simple memory allocator - Arjun Sreedharan

- http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/academic/class/15213-f10/www/lectures/17-allocation-basic.pdf

- Syscalls used by malloc.

- Understanding glibc malloc – sploitF-U-N

malloc variants

tcmalloc

- Optimized for high concurrency situations. The tc in tcmalloc stands for thread cache.

- Page-oriented, meaning that the internal unit of measure is usually pages rather than bytes.

Writing your memory management system

- Comes from this comment by Synthrea

- Step 1

- Get the map of physical memory freely available to your OS from BIOS/UEFI/your boot loader (e.g. by using the E820 call).

- Step 2

- Set up your frame allocator or physical memory manager by handing those free pages to it.

- You could use a linked list or a bitmap for this

- I would personally recommend implementing a buddy allocator

- It is much easier to allocate huge pages or continuous physical memory using a buddy allocator.

- You will need continuous physical memory for certain DMA requests too.

- This would essentially have an alloc that would take an order (i.e. a power of two size)

- Find the smallest possible page that satisfies the request

- Split it into buddies until it is the correct order and return the chunk, and a free that would free the chunk and merge buddies back into the highest order possible.

- Step 3

- Implement functions that help you manage your page tables.

- You want to have some kind of API that allows you to iterate over the PTEs given a virtual address range and call a function for each of them.

- This would allow you to quickly

unmapa range by simply freeing the pages and the page tables (once they become empty), and map a range by simply allocating page tables and pages. - You can also decide here to map in huge pages instead of a page table if you have to map in 2M worth of pages.

- You need a look up function for individual virtual addresses to use in your page fault handler to implement demand paging.

- Step 4

- Implement VMAs and demand paging.

- Instead of eagerly mapping in pages into the virtual address space, you will want something like a red-black tree or even just a sorted link list of VMAs

- The areas of virtual memory and what kind of memory they should be backed

- what kind of protection they need, etc.

- This way you can skip mapping in memory for userspace and just create a new VMA and insert it into the RB-tree.

- Once userspace tries to access unmapped memory, you simply look up if there is a VMA for the given fault address in the page fault handler and allocate physical memory to back the fault address (and populate the page from a file, if it is backed by a file). Don’t do this for your kernel, though.

- Step 5

- Drivers will need access to memory-mapped I/O, i.e. device registers and memory that live in your physical address space.

- You need page table management functions to map in MMIO as uncachable memory.

- Step 6

- At this point you should be able to map in memory at the granularity of 4K, possibly 2M or 1G if you huge/large page support.

- Most objects used by the kernel and userspace are much smaller than that.

- This is why you would implement something like a slab allocator

- Which subdivides a chunk of pages into n objects of the same size w a header/footer that tells you which objects are free.

- e.g. you would use this to allocate the VMA structs themselves.

- Step 7

- For userspace you can also decide to implement a slab allocator.

- For objects of 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, probably somewhere up to 4K you can rely on slab allocators and anything larger you can just decide to map in 4K pages directly.

- In order to support

malloc/free, you have to put in some header too that tells you what you allocated and how big the allocation is, becausefreedoesn’t get the size.

- Other tips

- Chicken and egg problem between setting up physical and virtual memory, because you need to allocate page tables from physical memory.

- You would start with a small identity mapping of e.g. the first GiB of memory being mapped to a fixed address in your virtual address space

- Then add the free physical pages to your buddy allocator.

- You can then use those to expand the identity mapping and the region of metadata used by the buddy allocator (some array of structs with information about the pages, that is used by the buddy allocator).

- Ideally you can delay this to a background thread to speed up the kernel boot time significantly on systems with lots of memory, as setting up the buddy allocator/identity mapping on a system with 2 TiB RAM is going to take a while, for example.

- Feel free to use quick and dirty hacks like having a fixed number of VMAs per process by having static arrays all over your kernel as you implement the different memory components

- so you don’t have to care too much about how to allocate a VMA until you actually have code for a slab allocator.

- Similarly just focus on 4K pages in the beginning, and you even may want to start with linked lists instead of a buddy allocator/RB-tree to grasp the general picture first.

- Also if this is in C, be ready to pull your hairs out, because linked lists are annoyingly frustrating to work with.

- My next kernel would definitely be in a language like Rust that has the intrusive collections crate to make it a lot nicer.

- I am pretty much assuming you are writing a modern 64-bit kernel where you set up the APIC and everything

- so you will definitely need something like an identity mapping and the ability to map in MMIO then.

- 32-bit is slightly different, especially due to the limited space of virtual memory, which easily leads to memory pressure

- especially on systems with PAE that can address 36 bits of physical memory or even more and where you can’t have a complete identity mapping anyway.

- In terms of files, my advice is to embed either ELF-files directly into the kernel so you can actually get to userspace and scheduling quite quickly without having to implement IDE or AHCI + some file system driver + a virtual filesystem layer.

- Alternatively, you can load files via the boot loader and provide them to your kernel, or rely on UEFI to load them initially.

- This way you can easily implement all the cool features like userspace, scheduling, even SMP and swap, etc.

- Of course, there is no right and wrong. The most important things are to learn and to have fun.

- Chicken and egg problem between setting up physical and virtual memory, because you need to allocate page tables from physical memory.

Other resources

Arena

- https://nullprogram.com/blog/2023/09/27/

- https://www.rfleury.com/p/untangling-lifetimes-the-arena-allocator

- https://www.rfleury.com/p/enter-the-arena-talk