tags : Computer Memory, Filesystems

All of this is linux specific

Memory Management

- It’s not exact science, everything is tradeoff between performance and accuracy.

- Example: If you limit memory it might affect disk I/O because it’ll start evicting the page cache and start using swap.

- Concepts overview — The Linux Kernel documentation

Virtual Memory

Only the kernel uses physical memory addresses directly. Userspace programs exclusively use virtual addresses.

Why do we need it

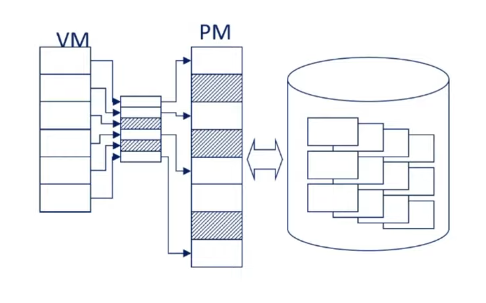

- Modern computers run multiple tasks, directly from/to physical memory is a bad idea because each program would request its own contagious block.

- We don’t have enough memory to give each program its own contagious memory, so we give it non-contagious and slap virtual memory on top of it

- It tricks the program to thinking that it has contagious memory now

- That too till the end of the virtual address space, not just till the end of physical memory. Big W.

- So essentially, we hide the fragmentation from the program by using virtual memory.

- A translation from physical to virtual address happens and vice-versa.

- This non-contagious memory, which appears to be contagious may be spread across, disk, physical memory, cache, or may even not be physically represented etc.

How is it implemented?

- Segmentation

- Page Table/Paged Virtual Memory

Paging

Paging is an implementation of virtual memory that the Linux kernel uses.

This topic should have been under virtual memory or Kernel but it’s a big enough topic so let it have its own Heading. But details will be specific to linux kernel.

See Memory Allocation and Memory Design and Memory Hierarchy

Components

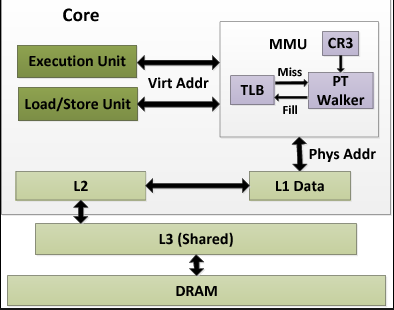

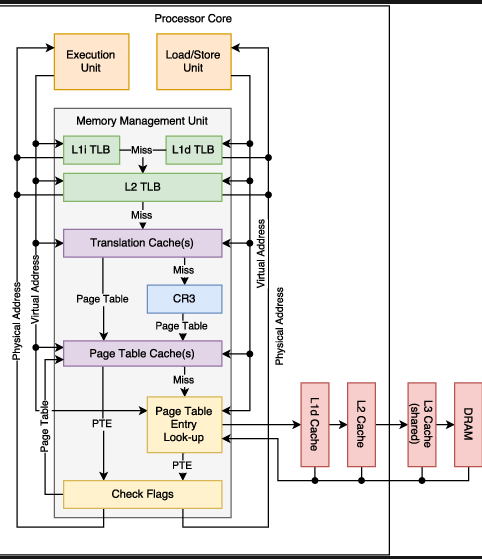

MMU

-

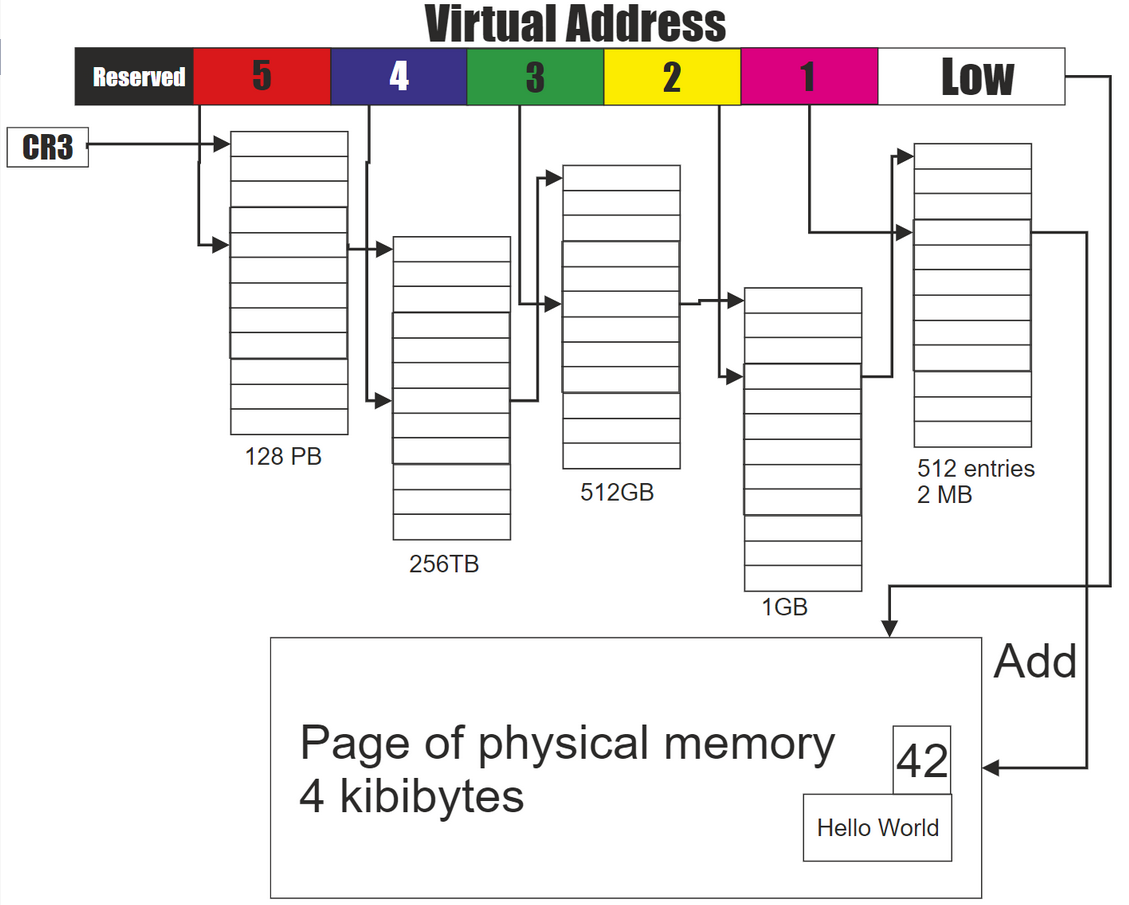

Page Table and Directory

- In theory, MMU sits between CPU and memory but in practice, it’s right there in the CPU chip itself.

- The MMU maps memory through a series of tables which are stored in RAM.

- Page directory (

PD), Pointed by Page Table Base Register (PTBR), PTBR stored atCR3 - Page table (

PT), Contains Page Table Entries (PTE)

- Page directory (

- Now there are even systems which do not have a MMU, The linux memory management system for it is called

nommu

-

Isolation and protection

- Paging is possible due to the MMU which is a hardware thing

- Paging provides HW level isolation ( memory protection )

- User processes can only see and modify data which is paged in on their own address space.

- System pages are also protected from user processes.

-

TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer)

- Memory cache in the

MMU - If there is a TLB miss, it’ll trigger a

page walk(Search down the page table levels to look for entry) - Invalidating a TLB entry flushes the associated cache line.

- Stores recent translations of virtual memory to physical memory.

- The majority of desktop, laptop, and server processors include one or more TLBs

- Applications with large memory WSS will experience performance hit because of TLB misses.

- See MMU gang wars: the TLB drive-by shootdown | Hacker News

- Memory cache in the

-

Page Fault Handler

- Page Fault Handler is a ISR/Interrupt Handler (See Interrupts)

- Called by MMU when we see a “page fault”

- 3 responses

- Soft/Minor faults: Updates things in memory, just the PTE needs to be created.

- Hard/Major faults: Needs to fetch things from disk

- Cannot resolve: Sends a

SIGSEGVsignals.

- If a page fault happens in the ISR, then it’ll be a “double fault” and kernel will panic.

- Triple fault? bro ded.

Pages

- Also called virtual pages , and block (see Block below)

- Usually the allocator deals with this and not user programs directly.

- Usually 4-64 KB in size (Huge Pages upto 2MB/1GB)

- May or May Not be backed by a

page frame - Some architectures allow selection of the page size, this can be configured at the kernel build time

λ getconf PAGESIZE

4096Blocks

pagesize = blocksize(SometimePagecan simply refer to theBlock)

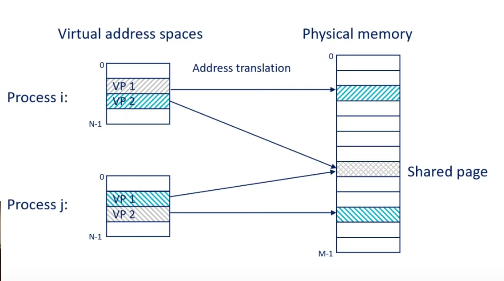

Page Frame

- Also called Frame / Physical Memory Page

- This is actual physical memory(RAM)

- A page frame may back multiple pages. e.g.shared memory or memory-mapped files.

Page Table

-

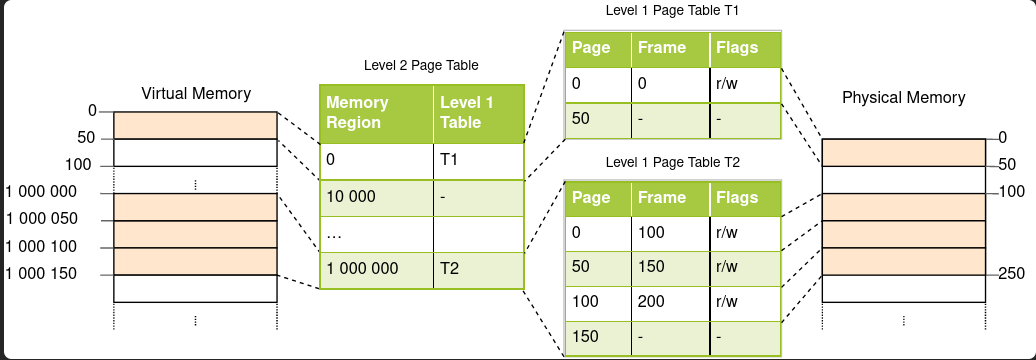

Essentially data structure that maps virtual address to physical. (unidirectional, virtual address -> physical address)

-

Kernel maintains per process page table, kernel also has a few page table for things like disk cache.

-

Stored in the RAM.

-

Kernel may have multiple page tables, active one is the one pointed by

CR3 -

Organized hierarchically(multi-levels) to reduce waste in memory

| block | page frame |

|---|---|

| 1 | 13 |

| 2 | 76 |

| 3 | 55 |

- Steps in accessing memory via page table

- Access requested for

block 3 - MMU intercepts & looks up page table to find the corresponding page frame

- Generate a physical address, pointing to

55th page framein the RAM.

- Access requested for

- An access memory location can be

- An instruction

- Load/Store to some data.

- Additional links

Important Features

Demand Paging

- This is used by both Standard IO and Memory Mapped IO. See O

- All pages are backed to disk, so starting on disk is similar to being swapped out

- OS copies a disk page into physical memory only if an attempt is made to access it and that page is not already in memory.

Locking Pages

- When a page fault occurs and kernel needs to do I/O for paging in

- Execution time of an instruction skyrockets

- We can Lock pages for programs that are sensitive to that. See

mlock

User process

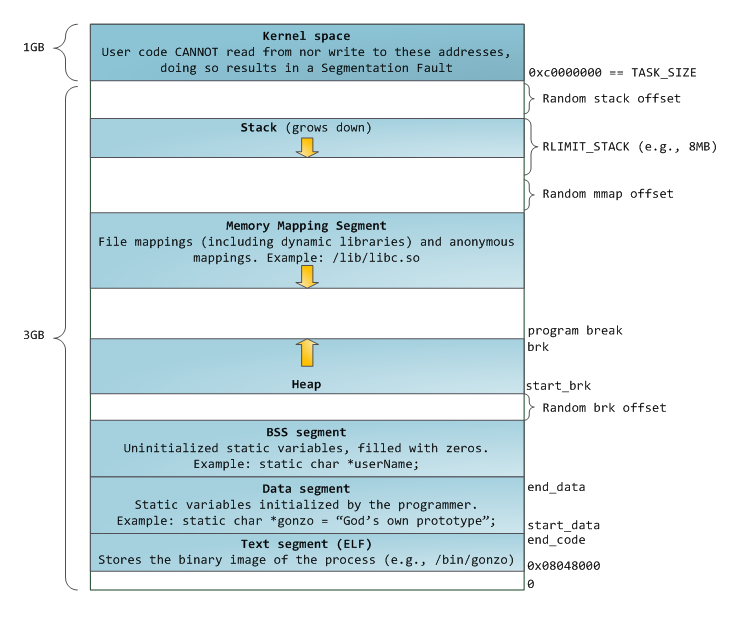

Virtual address space (VAS)

The VAS of a process consist of stack, heap, code, data, arguments etc.

The 3 and 1 GB split, is only for 32bit systems, rest of the image can be followed. For 64bit representation see this.

The 3 and 1 GB split, is only for 32bit systems, rest of the image can be followed. For 64bit representation see this.

printf("%p", &i); // shows virtual address- A process is represented by its VAS, a contagious address space from

addr0toMAX_SIZE. - When compiling with

gcc, thea.out(the executable) file contains information about how to create the virtual address space.

Virtual Addresses

The virtual addresses(block addresses) consists of two parts

table indexand theoffset.- The physical address is constructed from the

offsetand the page frame.

Shared resources

- A process has VMA holding information used to build its own page table

- This then points to a shared table and so on. (See page table levels)

- Example

- A process requests a for a

page - This actual

resourcemapped by thispagemay be in RAM and mapped by other processes using it - The process that requested it does not have a PTE for it.

- It’ll take a soft page fault and establish PTE and go on.

- A process requests a for a

Memory Layout

See Memory Allocation Compilers use a technique called escape analysis to determine if something can be allocated on the stack or must be placed on the heap.

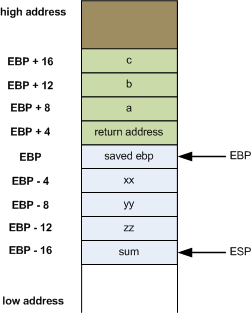

Stack

credit: eli’s blog.

ebp is the frame pointer/base pointer and esp is the stack pointer. When we say “top of the stack” on x86, we actually mean the lowest address in the memory area, hence the negative offset. esp points to the top of the stack.

rbpandrspare just the 64-bit equivalents to the 32-bitebpandespvariables.

Heap

Similar to the stack pointer(esp) the top of the heap is called the program break. Moving the program break up allocates memory and moving it down deallocates memory.

- Writing to higher addresses than the program break will result in segfaults for ovious reasons.

- Heap fragmentation can have a substantial impact on the CPU

- We can use syscalls to allocate heap, helper functions such as

mallochelp us call those underlying syscalls.

Programming language memory model

Python

- Every variable in python is simply a pointer to a C struct with standard Python object info at the beginning.

- Everything in Python is allocated on the heap.

- CPython does not make a syscall for each new object. Rather it allocates memory in bulk from the OS and then maintains an internal allocator for single-object

Golang

Memory Split

- Turns out that Go organizes memory in spans (idle, inuse, stack) (maybe outdated)

Stack size

- Go has is it uses its own non-C stack

- Go defaults to 2k while the smallest C stack I know of is 64k on old OpenBSD, then macOS’s 512k for the non-main threads

Other

- The memory models that underlie programming languages (2016) | Hacker News

- The Memory Models That Underlie Programming Languages | Hacker News

- The memory models that underlie programming languages

Kernel

Zones

- Hardware often poses restrictions on how different physical memory ranges can be accessed.

- In some cases, devices cannot perform DMA to all the addressable memory. In other cases, the size of the physical memory exceeds the maximal addressable size of virtual memory etc.

- Linux groups memory pages into zones to handle this.

- Full list: mmzone.h (See code comments) and official docs on phymem for details.

ZONE_DMA, ZONE_DMA32, ZONE_NORMAL, ZONE_HIGHMEM, ZONE_MOVABLE, ZONE_DEVICE

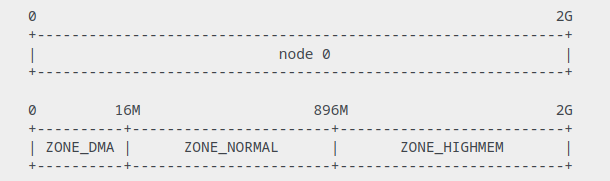

32bit (UMA)

64bit (NUMA)

ZONE_HIGHMEMis not really used in x64 anymore.- Is it time to remove ZONE_DMA? {LWN.net}

$ cat /proc/zoneinfo|rg Node

Node 0, zone DMA

Node 0, zone DMA32

Node 0, zone Normal

Node 0, zone Movable

Node 0, zone DevicePaging reclaim and memory types

Reclaim

- Reclaim : Try to free a page. Unload stuff memory. Make space for new stuff.

- Reclaimable memory is not guaranteed

- We need to ask when is it reclaimable, because it’s not a binary option

- Some page types maybe totally unreclaimable like some kernel structures.

- Some page in the cache might be super hot and reclaiming them makes no sense

- Sometimes you need to do something else before you can reclaim, eg. flush dirty pages.

- How?

kswapdreclaim : Background kernel thread, proactively tries reclaiming memory- Direct: If

kswapdwas sufficient, we’d never need direct reclaim. Direct reclaim usually blocks application as it tries to free up memory for it.

Memory types

There are semantics in linux that are specific to the pages that CPU is not aware of.

- Anonymous (non file-backed) memory/pages

- Not backed by anything.

- Created for program’s stack and heap or by explicit calls to

mmap(2)/malloc - If memory gets tight, the best the OS can do is write it out to

swap, then back in again. Ick. - Read Access and Write Access

- When the anonymous mapping is created, it only defines virtual memory areas that the program is allowed to access.

- Read accesses: Will create a

PTEthat references a special physical page filled withzeroes. - Write attempt: A regular physical page will be allocated to hold the written data. The page will be marked dirty and if the kernel decides to repurpose it, the dirty page will be swapped out.

- Backed pages

- Executable on disk mapped into RAM so you can run your program.

- Dirty backed pages

- Pages in the

page cachewhich have been modified and are waiting to be written back to disk. - If we want to reclaim a dirty page, we need to flush it to disk first.

- Pages in the

- Cache and buffers

- Pages responsible for caching data and metadata related to files accessed by those programs in order to speed up future access.

Huge Pages

“It’s funny how this moves in circles: Automatic merging into hugepages (THP) is added to the kernel. Some workloads suffer, so it gets turned off again in some distributions (not all of course). But for many different workloads (some say the majority), THP is actually really, really beneficial, so it is ported to more and more mallocs over time. It might have been more straightforward to teach the problematic workloads to opt out of THP once the problems were discovered.”

- Someone from orange site

- Essentially larger page allocation.

- Suppose TLB is 1MB and your program WSS is 5MB. TLB will obviously take hits. To get around this, we can use Huge Pages. It reduces pressure on the

TLB, The CPU has a limited number of TLB entries. This allows a single TLB entry to translate addresses for a large amount of contiguous physical memory. - Eg. with just one 2MB page you can cover the same amount of memory as with 512 default 4KB pages. And guess what, you need fewer translation entries in the TLB caches. It does not eliminate TLB misses completely, but greatly increases the chance of a TLB hit.

- In linux 2MB and 1GB pages are supported.

- Has tradeoffs as usual. Look them up. To have performance problems you need to use large amounts of memory with small allocations and not only that, but also free some to cause fragmentation.

$ cat /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled [always] madvise never $ cat /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages/hugepages-1048576kB/nr_hugepages 0

HugeTLB filesystem / hugetlbfs

- A pseudo filesystem that uses RAM as its backing store

- Hugepages need contiguous free physical pages. Without preallocating them at boot time, with higher system uptime, chances of finding such region to satisfy the allocation are slimmer, especially for 1G pages, to the point when even services starting later at boot time might not get them due to external fragmentation caused by 4k pages allocations.

- A database server seems like the ideal use case for (real) huge pages: a single application with a low-ish number of threads on a machine with a huge amount of RAM. Lots of page table misses with normal sized pages, but very little memory wasted from huge pages and no memory contention from other software.

Transparent HugePages, or THP

- Need to be enabled for programs via

madvice(). So that only THP aware applications can use it. - More modern, requires less configuration, kernel handles stuff

- THP can be massive source of bugs, weird behaviors, and total system failures

- Currently THP only works for anonymous memory mappings and tmpfs/shmem

- Transparent Hugepages: measuring the performance impact - The mole is digging

- kcompacd0 using 100% CPU with VMware Workstation 16

- Transparent Huge Pages: Why We Disable It for Databases | PingCAP

echo never > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/defrag echo 0 > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/khugepaged/defrag echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/compaction_proactiveness # default 20

More on Hugepages

- Hugepages and databases working with abundant memory in modern servers - YouTube

- Reliably allocating huge pages in Linux

- One could just plug in Google’s tcmalloc maybe https://github.com/google/tcmalloc. Also see

GLIBC_TUNABLES=glibc.malloc.hugetlb - Temeraire: Hugepage-Aware Allocator | tcmalloc

Allocation

- Linux uses both the buddy allocator and the slab allocator for different types of memory allocations in the kernel. (This is extremely generalized)

- The SLUB allocator {LWN.net}

- SLQB - and then there were four {LWN.net}

- The Slab Allocator in the Linux kernel (SLOB)

- A memory allocator for BPF code {LWN.net}

- A deep dive into CMA {LWN.net}

- The slab and protected-memory allocators {LWN.net}

- See Memory Allocation

Swap

Why we need swap

- In modern OSes, no such thing as free memory.

- If RAM is unused, that means it’s being wasteful/not being efficient. It’s a computer, it doesn’t get tired, you can keep running it. So your goal is to use RAM as much as possible and yet keep the system healthy.

- Kernel tries to help you do this w

swap, you can also turn it off if needed.

- swapping is not a bad thing. swap thrashing is bad - it means you need more memory.

- In defence of swap: common misconceptions

- Help! Linux ate my RAM!

What it is/ How does it help?

- Swap provides a backing store for them(anonymous memory doesn’t have a place to go back to so goes to swap).

- We might want to disable swap for certain/main “workloads” but we still want it for the whole system. (Eg. Elastic, Kubernetes)

- Things that swap is good at, you can’t get them any other way. Having big memory makes no difference.

- Gives us time for memory contention to ramp up gradually

- You also cannot reclaim/evict anonymous memory if there is no swap!

- Swap allows reclaim on types of memory which otherwise be locked in memory.

- If we want to swap out

anonmemory for something else, now(if noswapspecified) we’re just going to thrash thepage cacheto make space for it, which might be worse because we might have to reclaim/evict actual hot page to make space for it.

- One thing to be aware of however is that, it can delay invocation of OOM killer. This is why we need things like

oomd/earlyoom - It is what allows your computer to go into hibernation(suspend to disk). (Sleep and Hibernation are different brah)

What it’s not and misconceptions

- It is not for emergency memory. It is how virtual memory works in linux.

- Not using swap does not magically make everything happen in memory. Kernel still has to flush things to disk, file backed memory as an example. See O

Swappiness

- One of the answers to the “memory is availbl, y r tings on swap?” question.

vm.swappiness: It’s the kernel’s aggressiveness in preemptively swapping-out pages.- Range:

0-100 0use memory more, use swap less100use memory less, use swap more- The default value is

60(sysctl -a|sudo rg swapp)

- Range:

FAQ

-

Memory available, but why are things on swap then?

- If swapping happens, that does not necessarily mean that there is memory is under-pressure.

- If the kernel sees that, okay this portion is not getting used so often, i’ll just put it in swap for now. So that I can make space for other stuff immediately.

- Eg. If your swap is 100% and memory at 60% then either

- Your

swappinessvalue is wrong - You need more swap space

- Both of the above.

- Your

- NEED MORE INFO

-

If excessive swap is fine, when to worry?

- If swap size is too big (because kernel will keep thrashing things and you’ll never know)

- If pages are being swapped because of memory pressure

-

How to fine-tune swap

- Disabling Swap

- Disabling swap for individual processes (Using things like cgroups)

- Use

mlock(caution! not really a good usecase) vfs_cache_pressure: for caching of directory and inode by swapping

-

What if I am using a network backed storage?

Then I guess it makes sense to disable swap. Because latency will be off the roof. But you can probably just swappiness down and use something like

zswapinstead of totally disabling it.

Metrics for swap

- Swap Activity (swap-ins and swap outs)

- Amount of swap space used

Swapfile, Swap Partitions, zswap, zram

-

Swap partition

- No significant advantage of having a partition, might as well use just a swapfile

-

Swapfile

- With swapfile you can change the swap size later easily.

-

zram

- Kernel module (zram)

zswapandzramcannot co-exist. (zswaphas to be turned off if you want to usezram)- Can be used to create a compressed block device in RAM. Does not require a backing swap device.

- Usecases

/tmpreplacement- Using it as swap

- caches under

/var - More

- Hibernation will not work with zram

- Eg. 4GiB VPSs w 1 vCPU and slow IO

- Configure zram to aggressively compress unused ram with

lz4 - Decompressing gives orders higher throughput and lower latency than any disk swap can ever be

- Configure zram to aggressively compress unused ram with

-

zswap

- Kernel feature (zswap)

- Lightweight compressed RAM cache “for swap pages”. Works in conjunction with a swap device(partition or file)

- Basically trades CPU cycles for potentially reduced swap I/O

- It evicts pages from compressed cache on an LRU basis to the backing swap device when the compressed pool reaches its size limit. This is not configurable. More like plug and play.

Thrashing

In low memory situations, each new allocation involves stealing an in-use page from elsewhere, saving its current contents, and loading new contents. When that page is again referenced, another page must be stolen to replace it, saving the new contents and reloading the old contents. WSS takes a hit.

- Cache thrashing: Multiple main memory locations competing for the same cache lines, resulting in excessive cache misses.

- TLB thrashing: The translation lookaside buffer (TLB) is too small for the working set of pages, causing excessive page faults and poor performance.

- Heap thrashing: Frequent garbage collection due to insufficient free memory or insufficient contiguous free memory, resulting in poor performance.

- Process thrashing: Processes experience poor performance when their working sets cannot be coscheduled, causing them to be repeatedly scheduled and unscheduled.

OOM

An aircraft company discovered that it was cheaper to fly its planes with less fuel on board. The planes would be lighter and use less fuel and money was saved. On rare occasions however the amount of fuel was insufficient, and the plane would crash. This problem was solved by the engineers of the company by the development of a special OOF (out-of-fuel) mechanism. In emergency cases a passenger was selected and thrown out of the plane. (When necessary, the procedure was repeated.) A large body of theory was developed and many publications were devoted to the problem of properly selecting the victim to be ejected. Should the victim be chosen at random? Or should one choose the heaviest person? Or the oldest? Should passengers pay in order not to be ejected, so that the victim would be the poorest on board? And if for example the heaviest person was chosen, should there be a special exception in case that was the pilot? Should first class passengers be exempted? Now that the OOF mechanism existed, it would be activated every now and then, and eject passengers even when there was no fuel shortage. The engineers are still studying precisely how this malfunction is caused.

- The Linux OOM is Reactive, not proactive. It’s based on reclaim failure, which is the worst case. So things are usually bad when the OOM kicks in.

- Our goal is to avoid having to invoke oom killer at all and to avoid memory starvation. OOM Daemon helps.

- OOM itself is not even aware of what it is even killing, it just kills. So if the memory congestion issue needed proccess X to be killed, OOM might just kill Y.

Why linux does know when it’ll be out of memory?

- Things might be in cache and buffer which probably cannot be evicted/reclaimed.

- So, even if there are a lot of cache and buffers available, if the kernel decides that there are important things in these it will not evict them! Therefore you system might go out of memory even if it has stuff in cache and buffer.

- So the only way to know how many pages can be freed is via trying to reclaim the pages.

- So when the kernel tries to reclaim memory and fails for a long time it realizes it’s out of memory.

OOM Daemon

- Because of OOM never triggers on time because it realizes that it’s out of memory too late, we need something else, come OOM Daemons.

- OOM Daemons are based on memory pressure instead.

- OOM Darmons can kill things before we actually run out of memory.

- Context aware decisions (We can exclude certain things from getting oomed, eg. ssh sessions)

- Kills when killing is needed

- More configurable than kernel oom

- Eg. Facebook oomd, systemd-oomd(based on oomd), earlyoom

Cache

See Caches

Buffer cache

- Sits between the FS and disk

- Caches disk blocks in memory

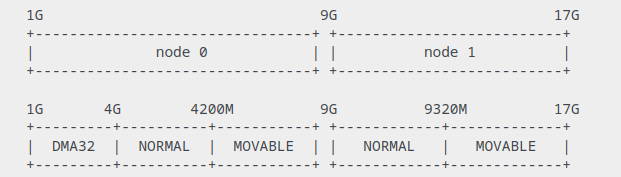

Page cache

- Sits between the VFS layer and the FS

- Caches memory pages

- Major part in I/O

- Whenever a file is read, the data is put into the page cache to avoid expensive disk access on the subsequent reads.

- When one writes to a file, the data is placed in the page cache and eventually gets into the backing storage device.

- See O

- No need to call into filesystem code at all if the desired page is present already.

- The future of the page cache {LWN.net}

Unified cache

- Ingo Molnar unified both of them in 1999.

- Now, the

buffer cachestill exists, but its entries point into thepage cache - Logic behind Page Cache is explained by Temporal locality principle, that states that recently accessed pages will be accessed again at some point in nearest future.

- Page Cache also improves IO performance by delaying writes and coalescing adjacent reads.

Skipping the page cache with Direct IO (O_DIRECT)

-

When to use it

- It’s not generally recommended but there can be usecases. Eg. PostgreSQL uses it for

WAL, since need to writes as fast as possible(durability) and they know this data won’t be read immediately.

- It’s not generally recommended but there can be usecases. Eg. PostgreSQL uses it for

-

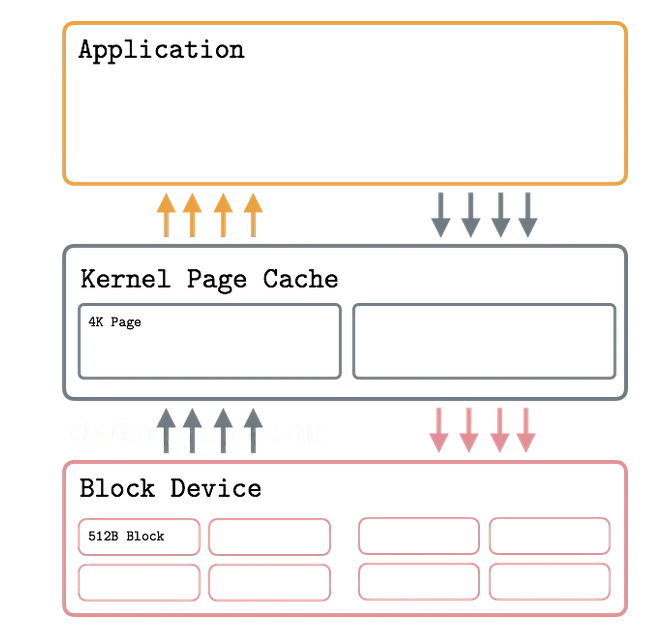

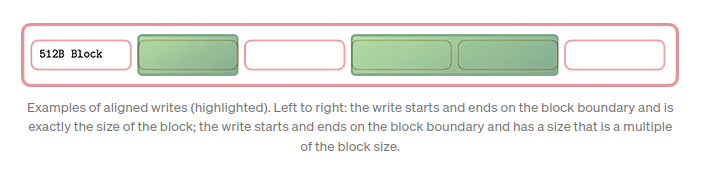

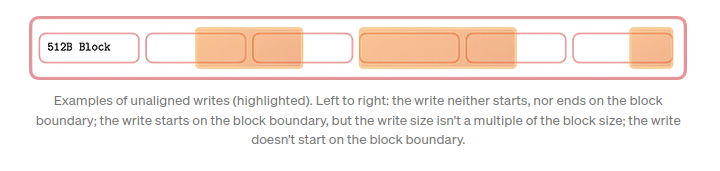

Block/Sector Alignment

When using page cache, we don’t need to be worrying about aligning our data, but if we doing direct IO, we better do.

Controlling Page Cache

- cgroups can be used

fadviceandmadvicesysalls

Other notes

- writeback throttling

Slab

- See Memory Allocation

- Linux kernels greater than version 2.2 use slab pools to manage memory above the page level.

- Frequently used objects in the Linux kernel (buffer heads, inodes, dentries, etc.) have their own cache. The file /proc/slabinfo gives statistics on these caches.

Memory Fragmentation

- Linux Kernel vs. Memory Fragmentation (Part I) | PingCAP

- Linux Kernel vs. Memory Fragmentation (Part II) | PingCAP

Memory overcommit

- People who don’t understand how virtual memory works often insist on tracking the relationship between virtual and physical memory, and attempting to enforce some correspondence between them (when there isn’t one), instead of controlling their programs’ behavior. (copied from the great

vm.txt) vm.overcommit_memorycan be set 0,1,2. RTFM.- By default,

vm.overcommit_ratiois50. This more like the percentage

Resources

- Is RAM wiped before use in another LXC container? | Hacker News (Answer is yes and no, memory is wiped before allocating not on free but can be configured and depends on system)

- Size Matters: An Exploration of Virtual Memory on iOS | Always Processing

- Memory Allocation | Hacker News 🌟

- Screwing up my page tables | Hacker News

- How does KERNEL memory allocation work? Source Dive 004 - YouTube