tags : Operating Systems, Threads

FAQ

Program v/s Processes

Program is the code you write, Process is the running instance of your program. That is, your program gets loaded into memory, registers from the processor are assigned to complete the execution of the process(your program).

Does killing the parent kill the child?

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

pid_t child_pid = fork();

if (child_pid == -1) {

// Fork failed

perror("fork");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

} else if (child_pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("This is the child process.\n");

// Additional child process logic goes here

sleep(5); // Sleep for 5 seconds to simulate some work

printf("Child process completed.\n");

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

} else {

// Parent process

printf("Parent process, exiting. Child PID: %d\n", child_pid);

// Parent-specific logic goes here

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

}- Not really. But this is confusing because when we exit a shell the child processes get terminated. This does not explain the true behaviour of parent and child. If a child dies when the parent dies, something is informing the child about it and the child can die then if it wants.

- Even if the parent process voluntary exists, or some external signal terminates the parent (

SIGKILL,SIGHUPetc.), if the parent is not sending those signals to the child, the child will live on. - Once the parent is terminated, child becomes orphaned and gets picked up by

init(pid1).

Unix process hierarchy

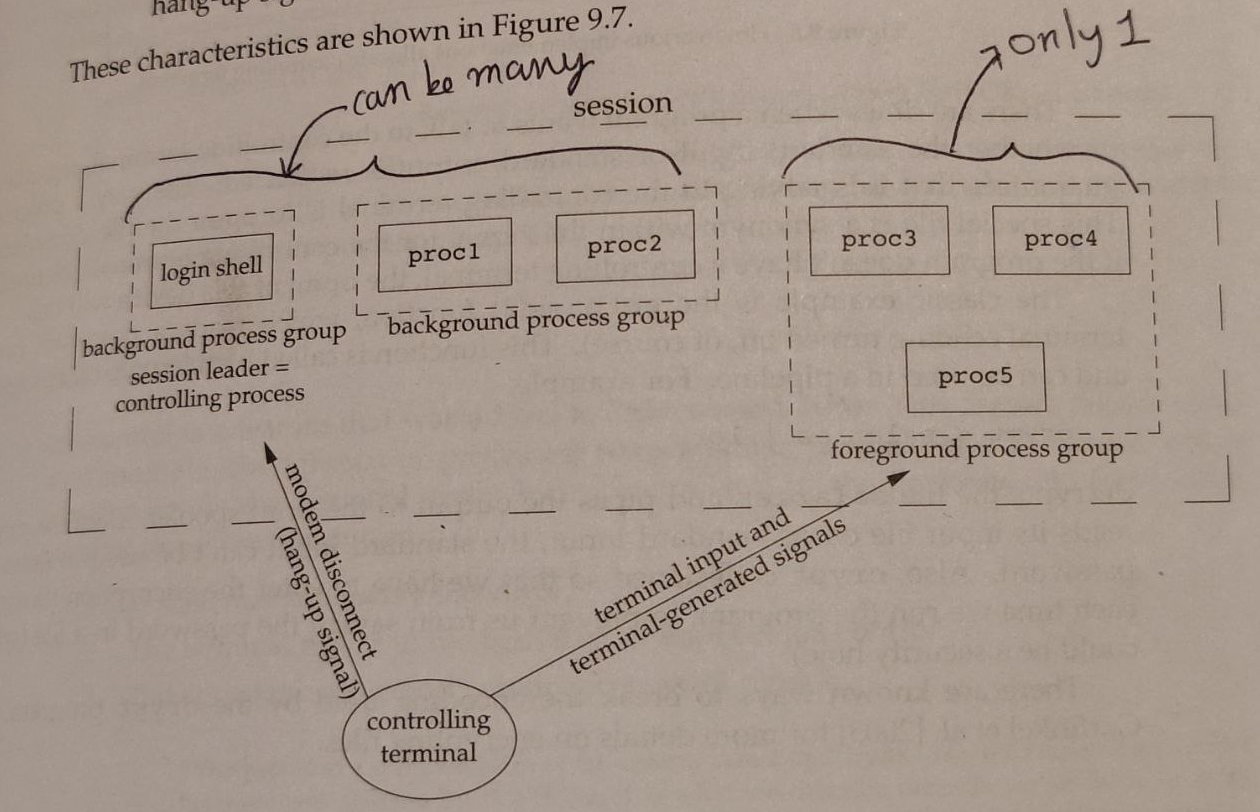

Session (SID) → Process Group (PGID) → Process (PID)- Unix every process belongs to a group which in turn belongs to a session.

- Data type for

pidandpgidis the samepid_t

Process

- These have

pid

Process Groups

- A

process group leaderis just a normal process whereits pid == its pgid. - So, when creating a new process group, we’ll always have a

process group leader. Thepidof the calling process becomes thepgidof the newprocess groupand it becomes theprocess group leader. - Once we have a

process group leader, we have apgid, we have aprocess group. - Once there is

pgidin the system, the original process(theprocess group leader) with thepid = pgidcan terminate and theprocess groupwould still exist till the lastprocessof thatpgidexists.

Sessions

- There is nothing called

session id session IDis thepid of the session leadersession leaderscan have one singlecontrolling terminal- When we close the terminal window, a

SIGHUPis sent to thesession leaderfor that terminal. Thesession leaderprocess then sendsSIGHUPto child processes etc.

Creating new session

- Using

setsid - If calling process is a

process group leader, error out. - If calling process is NOT a

process group leader- New

sessionis created - caller process becomes the

session leader - New

process groupis created - caller process becomes the

process group leader - No

controlling terminalis attached, if there exists one, it’s detached.

- New

Types of processes

Ways to create a new process

- Windows API provides the

spawnfamily, Linux does not provide in one step. Instead it givesfork()and theexec()family of functions. fork()returns twice, once in the parent and once in the child. It basically clones p1 to p2, p2 runs the program.exec()exec functions replace the program running in a process with another program.- When we

exec(), it blanks the process’s current page table, discarding all existing mappings, and replaces them with a fresh page table containing a small number of new mappings- An executable

mmap()of the new file passed to theexec()call. - env vars and command line arguments, same pid, a new process stack, and so on.

- An executable

- That’s why to launch a new process in Unix-like systems, we do

fork(), followed immediately by a call toexec()(execve()) - See syscalls where this is described better.

- When we

Zombie/defunct processes

- Parent process needs to

wait/waitpidon the child to “reap” it once it terminates. Otherwise it’ll become zombie. - A child that terminates, but has not been waited for becomes a “zombie”.

waitis usually blocking, but can pass certain flags to make it async which is probably more prefered.- We can also wait for the

SIGCHLDsignal. (See Signals)

Background process (&)

- For interactive shells

- Forks and creates a new process group

- So as not to be in the terminal’s foreground process group

- For non-interactive shells

- Forks a process and ignores SIGINT in it.

- It doesn’t detach from the terminal, doesn’t close file descriptors

Daemon process

- See Laurence Tratt: Some Reflections on Writing Unix Daemons

- In practice you’d use something like systemd but for the sake of what happens.

- You need certain things like not attached to terminal, don’t have a parent other than init, be in your own session, get rid of fds from parent, change working dir and so on. See Chapter APUE13.3.

// simplified version to create daemon process

// fork and also have the parent terminate

fork()

// because pid != pgid is guranteed after fork, setsid will work

// 1. new session, pid becomes sid (session leader)

// 2. new process group, pid becomes pgid (process group leader)

// 3. controlling terminal is detached

setsid()

// chdir to /, just in case parent process was in a mounted fs

chdir()

// close existing fd(s)

// set /dev/null as fd 0, 1 and 2

close(0)

close(1)

close(2)

// double fork (optional)

// - No longer session leader

// - No controlling terminal can be attached to the process now

fork()- Here the parent process would exit leaving the the child process behind. This child process detaches from the controlling terminal, reopens all of {stdin, stdout, stderr} to /dev/null, and changes the working directory to the root directory.

- Double fork, why?

Context switch

- Switching between different processes, the registers in the processor gets reassigned. Context switch can happen between

Kernel ModeandUser Mode. - The process context information is stored in the Process Control Block(PCB, a data structure used by the OS). When context switch happens kernel stores the PCB info and switches context and loads it back when switching context back and so on.

When switching modes from KernelMode to UserMode, state of p1 is saved and switched to p2. There are state changes among Running, Ready and Blocked, a blocked process cannot immediately become running, it has to be ready first.

An user process running means the dispacher isnt because cpu only run one thing at a time, the ways the OS gains control are as follows:

- Exceptions : sys calls, page faults, seg faults etc.

- Hardware intrrrupts : keyboard, network, ISR(Interrupt service routine).