tags : Programming Languages

Modules/Packages/Imports

- A

moduleis a python file, and apackageis a directory of modules with an__init__(Edit: and/or a__main__). - Even following the release of 3.3, the details of how sys.path is initialised are still somewhat challenging to figure out.

File loading

- Just knowing what directory a file is in does not determine what package Python thinks it is in.

- Since Python 2.6 a module’s “name” is effectively

__package__ + '.' + ___name__, or just__name__if__package__isNone

Two ways to load a Python file

- As top-level script

- When executed directly, for instance by typing

python myfile.py __name__:__main__

- When executed directly, for instance by typing

- As a module

- When an import statement is encountered inside some other file.

__name__: [the filename, preceded by the names of any packages/subpackages of which it is a part, separated by dots], eg.package.subpackage1.moduleX- NOTE: If you run

moduleXas the top-level script (eg.python -m package.subpackage1.moduleX), the__name__will instead be__main__. (Just a variant of top-level script) - The most important takeaway is that: the name of the module depends on how you loaded it.

- It doesn’t matter where the file actually is on disk.

- If a module’s name has no dots, it is not considered to be part of a package.

- Special case: REPL

- A special case is if you run the interpreter interactively, the name of that interactive session is

__main__- You cannot do relative imports directly from an interactive session.

- Python adds the current directory to its search path(

sys.path) when the interpreter is entered interactively.- This is why you’re able to do

import moduleX, if its in the same directory. - It will not know that the directory is part of a package.

- This is why you’re able to do

- A special case is if you run the interpreter interactively, the name of that interactive session is

Imports

Relative imports

- Relative imports are only for use within module files.

- Relative imports use the module’s name to determine where it is in a package.

- If your module’s name is

__main__, it is not considered to be in a package. You cannot use relative imports then.

Absolute imports

- Absolute imports were added later

Packages

- Technically, a package is a module that has a

__path__attribute.

Types

- Named packages

- Python 3.3+: supports implicit namespace packages that allows it to create a package without an

__init__.pyfile. - Python 2: You needed to do weird shit

- Creating a namespace package should ONLY be done if there is a need for it. i.e if you have different libraries that reside in different locations and you want them each to contribute a subpackage to the parent package.

- Namespace packages can exist in more than one place at a time, while regular packages cannot.

- Python 3.3+: supports implicit namespace packages that allows it to create a package without an

/usr/lib/python3.9/site-packages/

└── foobar/

└── nice.py

/usr/local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/

└── foobar/

└── wow.py- Regular packages

- A package with a

__init__.py(empty or not empty)- Leaving an

__init__.pyfile empty is normal, if the package’s modules and sub-packages do not need to share any code.

- Leaving an

- A directory with a C extension named

__init__.soor with a.pycfile named__init__.pycis also a regular package. - The

__init__.pyfile- Typically left empty

- Can contains package-related attributes such as

__doc__and__version__ - Can be used to decouple the public API of a package from its internal implementation.

- A package with a

Module

- Keep module names short, lowercase, and avoid special symbols like

_,.,- etc. - Don’t namespace with underscores, use submodules instead.

Glossary

- Python behind the scenes #11: how the Python import system works

- Module object: a Python object that acts as a namespace for the module’s names. The names are stored in the module object’s dictionary (available as

m.__dict__), so we can access them as attributes. - Built-in modules: C modules compiled into the python executable.

- Frozen modules: Part of the python executable, but they are written in Python. Python code is compiled to a code object and then the marshalled code object is incorporated into the executable.

- C extensions: A bit like built-in modules and a bit like Python files.

- Written in C or C++ and interact with Python via the Python/C API.

- They are not a part of the executable but loaded dynamically during the import.

- Some standard modules including

array,mathandselectare C extensions. asyncio,heapqandjsonare written in Python but call C extensions under the hood.

- Python bytecode:

- Typically live in a

__pycache__directory - They are the result of compiling Python code to bytecode.

- Its purpose is to reduce module’s loading time by skipping the compilation stage.

- Typically live in a

Different kinds of modules in use

- Built-in modules such as

osandsys - Frozen modules.

- C extensions.

- Python source code files or

pycfiles - Third-party modules you have installed in your environment

- Your project’s internal modules (directories)

How to import

# bad

from modu import *

x = sqrt(4) # Is sqrt part of modu? A builtin? Defined above?

# better

from modu import sqrt

[...]

x = sqrt(4) # sqrt may be part of modu, if not redefined in between

# best

import modu

x = modu.sqrt(4) # sqrt is visibly part of modu's namespaceOperation

import pack.modu , this:

- It’ll look for an

__init__.pyfile inpack, execute all of its top-level statements. - Then it will look for a file named

pack/modu.pyand execute all of its top-level statements. - Creates a

module objectfor thatmodule, and assigns themodule objectto thevariable.

Module object

- The type of a

module objectisPyModule_Typein the C code but it’s not available in Python as a built-in.

from types import ModuleType

# what type does

# import sys (could be any other module)

# ModuleType = type(sys)

# ModuleType

m = ModuleType('m') # this is what happens when we importIssues

Double import

“Never add a package directory, or any directory inside a package, directly to the Python path” The reason: every module in that directory is now potentially accessible under two different names

- As a top level module (since the directory is on

sys.path) - As a submodule of the package (if the higher level directory containing the package itself is also on

sys.path).

Namespace and Scope

- Existence of multiple, distinct namespaces means several different instances of a particular name can exist simultaneously

- To pinpoint to which variable we’re refering to from which namespace, we use

scope

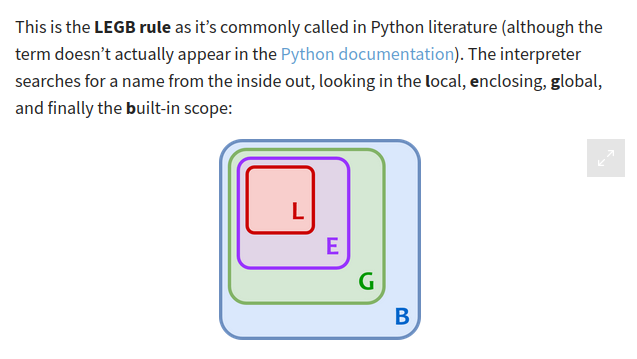

Types of namespaces

- Built-In:

__builtins__ - Global: One belonging to the main program

- Enclosing: Function enclosing another function

- Local: Namespace specific to a function

Scope

- It’s a runtime thing.

- scope of a name is the region of a program in which that name has meaning.

- As namespaces, scopes are: Local, Enclosing, Global and Builtin

- Accessing shit outside of scope

- It’s not advisable to use these, better to avoid

globalnonlocal: nearest enclosing scope

Threading and Processes in Python

Daemon threads and non-daemon

- This is different from the unix idea of a daemon. Don’t confuse.

- non-daemon thread (blocking)

- starts running in background and you can perform other stuff

- your program or main thread is blocked by non-daemon threads

- main thread will not exit until all such non-daemon threads have completed their execution

- daemon threads (non-blocking)

- As soon as the main thread completes its execution & the program exits, all the remaining daemon threads will be reaped.

- Your program or main thread is NOT blocked by daemon threads

Threads vs Processes and GIL in Python

- There’s a GIL per process, so no GIL limitations when using processes

- Processes good for CPU bound tasks as they can use multiple CPUs if available

- Threads good for I/O bound shit (See O). But limited by GIL, only one thread at a time.

GIL is a lock

- Allows only one thread at a time to execute

- Needed in Cpython because memory management is not threadsafe because it uses ref counting Garbage collection

OOP

Object lifecycle

- Read later: All about Pythonic Class: The Life Cycle

- One of the 3

- A prototype

- A objects of some other classes

- A

metaclassof type. Eg. <class ‘str’> : <class ‘type’>

__init__is not a constructor__new__is a constructor: This is called before__init__selfparameter- Interpreter passes the

created objectitself as the first argument into__init__, by convention it’s calledselfbut you could call it anything

- Interpreter passes the

metaclass: takes properties from other classes to generate a new class with additional functionalities.

Other terms

super(): Gives access to the class it inherits from

Dataclasses

- Dataclass also has a self-documentation effect: it says “this thing is kind of like a record“.

- There are debates around whether classes should be replaced with dataclasses in python etc. at the end of the day the ans is it depends and see if things fit etc etc.

- Pydantic has dataclasses too, but does validation and bunch of other stuff which makes it slower and rightly so.

- Internet comments

- I think kw_only=True and slots=True solve a lot of my dataclass problems. Wish they defaulted to true

Abstract classes vs NotImplementedError

- Basically ABCs to describe the nature of the program, it doesn’t do runtime enforcement anyway but if the problem I am working on fits the nature of ABC I can use it

- Otherwise, if it’s just a case of me implementing a class that down the line someone else should implement then NotImplementError is good enuf and more appropriate imo

- python - When to use ‘raise NotImplementedError’? - Stack Overflow

Other basic shit

Expression vs Statement

- A statement in Python is a unit of code.

- An expression is a special statement that can be evaluated to some value.

Decorators

- Decorator pattern != Decorators (See Design Patterns)

- The Decorator Pattern

Serving Python as a Web Application

- See Web Server and Web Development

- In the past we used WSGI, now we use ASGI

- ASGI is a spec, implementations(server applications) include Daphne, Hypercorn and Uvicorn.

- These implementations (eg. Uvicorn) handle HTTP and pass parameters in dicts to some applications built with some

ASGI framework- If you deploy on AWS lambdas, you wouldn’t use Uvicorn or any of the other servers, only Mangum.

- FastAPI is a

ASGI Framework

Tuples and commas

yolo = {"a": [1,2,4], "b": [4,5,6]}

yolo['a'] # [1, 2, 4]

yolo['a'], # ([1, 2, 4],)

# lo karli wo waali baatRegular things to know

I’ll just list things here so that these are under my radar when they are new, when they become common things for me i’ll just remove them from this list

Stdlib

- collections.Counter

- collections.namedtuple, alternatively use

typings.NamedTuples(better imo) - collections.OrderedDict (less imp now, normal dict remember order)

- collections.defaultdict

- itertools.{product, permm, comb, comb_wr, groupby, count, cycle, repeat}

- functools.{reduce}

- queue.Queue : Useful for Concurrency stuff (It’s Thread Safe, i.e put and get call itself are atomic so you can be sure T2 will not take your queue item)

- There’s also multiprocessing.Queue

Language features

- type hints

- pattern mathiing

- walrus assignment experssion operator

- it can return the value being assigned, unlike normal assignments

- usecases

- debugging: evaluate things into identifiers mid other expressions

- intent when doing things

numbers = [2, 8, 0, 1, 1, 9, 7, 7] num_length = len(numbers) num_sum = sum(numbers) description = { "length": num_length, "sum": num_sum, "mean": num_sum / num_length, } # we can now do this instead description = { "length": (num_length := len(numbers)), "sum": (num_sum := sum(numbers)), "mean": num_sum / num_length, } - The := assignment expression operator isn’t always the most readable solution even when it makes your code more concise.

FP stuff

filter(None,[])- filter takes a function, not a value. filter(None, …) is shorthand for filter(lambda x: x, …) — it will filter out values that are false-y