tags : Linux, Systems, Filesystems, Object Store (eg. S3)

Physical Medium

- HDD

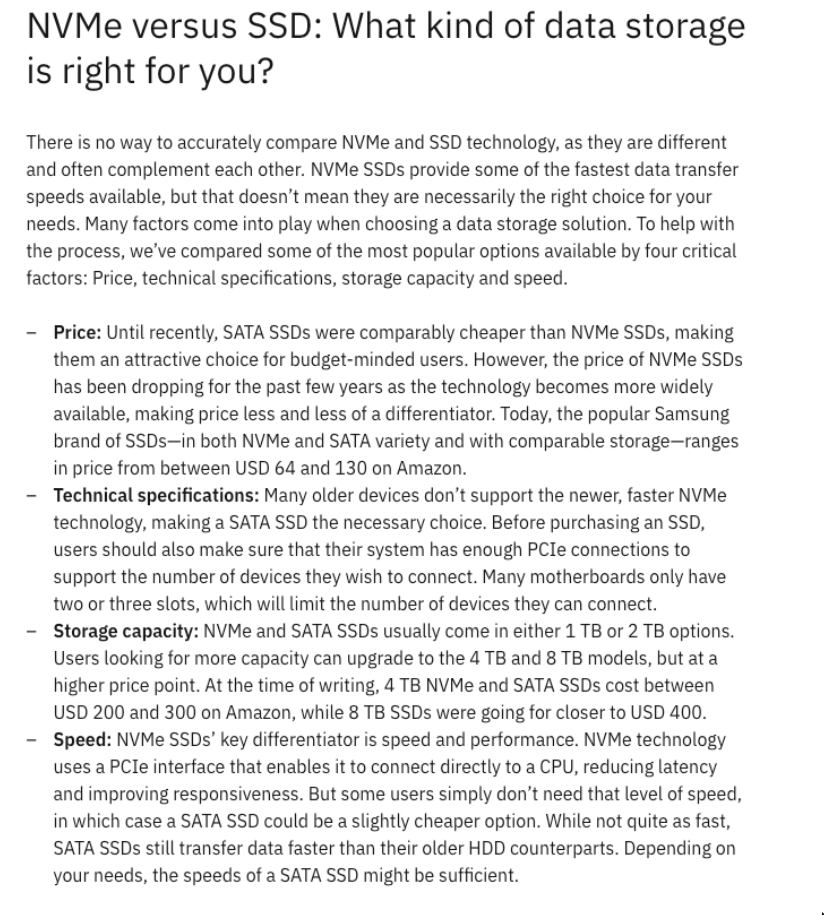

- SSD

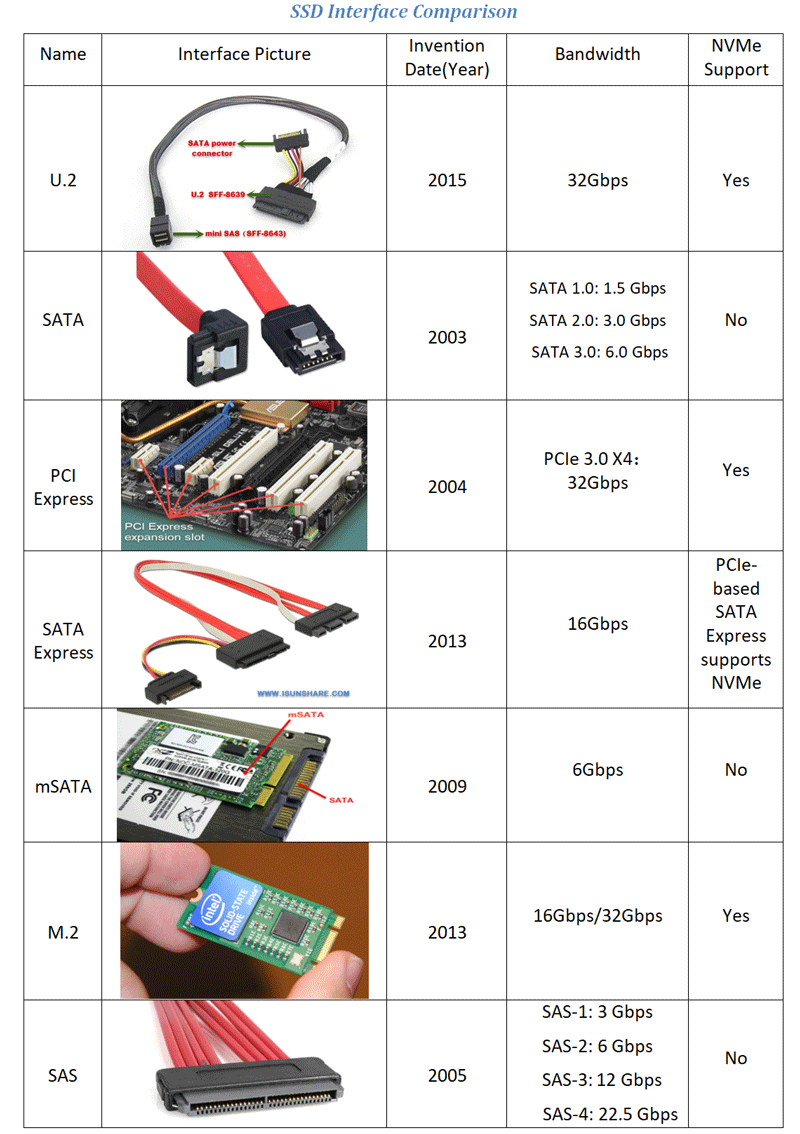

- Those devices have a connector that speaks a certain transfer protocol, which is usually a SCSI or ATA cable.

- Read more on this later: Data Storage on Unix

Storage Medium

- Attachment Packet Interface (ATAPI) disk

- Serial-Attached SCSI (SAS) disk

- Serial Advanced Technology Attachment (SATA) disk.

Storage layers

See Exta FS Info

Block layer

See Memory Hierarchy Block layer divides the storage device into fixed-sized “blocks” of contiguous memory

- HDD: Spinning platters & moving arms

- Tape: Single contiguous magnetic stripe.

- SSDs: Arrays of NAND flash

λ stat -f .

File: "."

ID: 4817ba2a119ea9a0 Namelen: 255 Type: ext2/ext3

Block size: 4096 Fundamental block size: 4096

Blocks: Total: 113739102 Free: 73843814 Available: 68047808

Inodes: Total: 28966912 Free: 26207344

λ sudo tune2fs -l /dev/sda3 | rg -i inode

Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype ...

Inode count: 28966912

Free inodes: 26207643

Inodes per group: 8192

Inode blocks per group: 512

First inode: 11

Inode size: 256

Journal inode: 8

First orphan inode: 26246587

Journal backup: inode blocksSuperblock

- Superblock is file system metadata (Eg. FS type, size, status, free and allocated blocks etc. and metadata of metadata). Critical to the FS, so redundant copies are stored.

Superblockis defined by theFSbut actually present in thepartition.- If the superblock of a partition

/varbecomes corrupt - The FS in question (

/var) cannot bemountedby the OS. - In this case you may need to run

fsckto pick a backup copy of the superblock and attempt to recover the FS.

- If the superblock of a partition

λ sudo dumpe2fs /dev/sda3 | rg superblock

dumpe2fs 1.47.0 (5-Feb-2023)

Primary superblock at 0, Group descriptors at 1-56

Backup superblock at 32768, Group descriptors at 32769-32824

...

Backup superblock at 78675968, Group descriptors at 78675969-78676024

Backup superblock at 102400000, Group descriptors at 102400001-102400056Layout

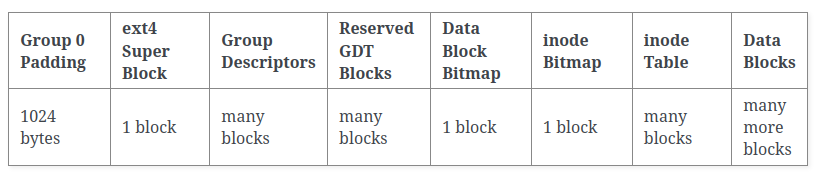

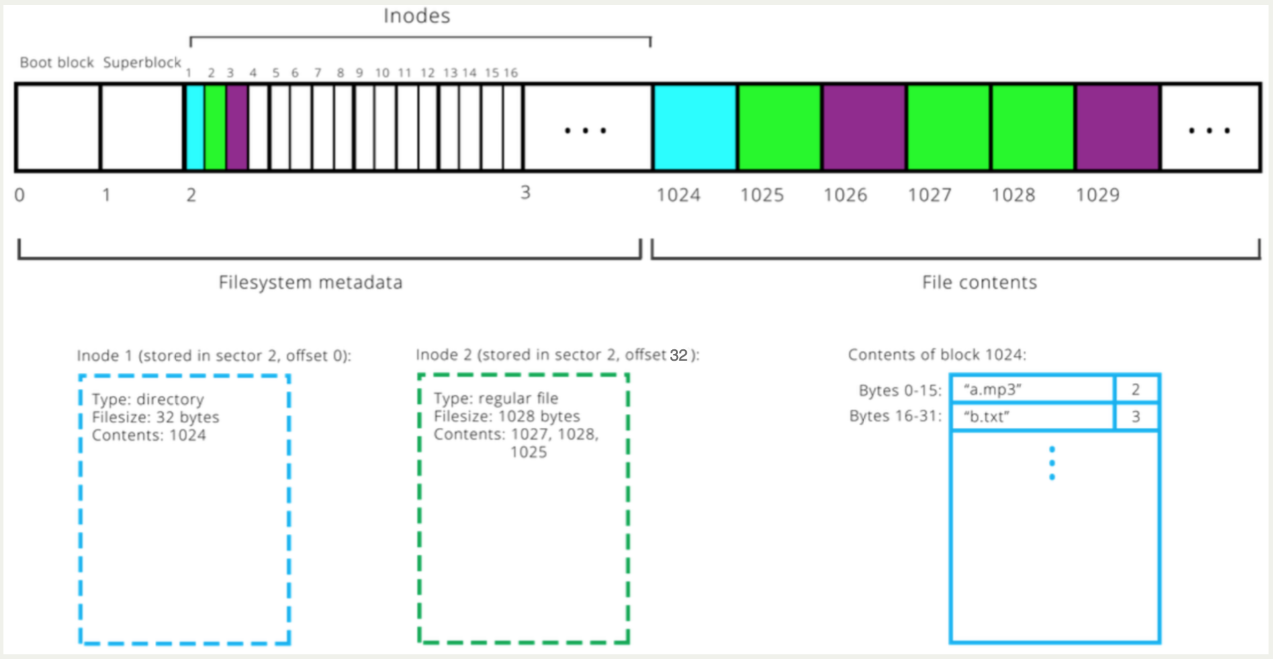

Layout is specific to FS. Let’s take EXT4 Layout for example. It has one inode table per block group which tracks only inodes in that group

File/inode layer

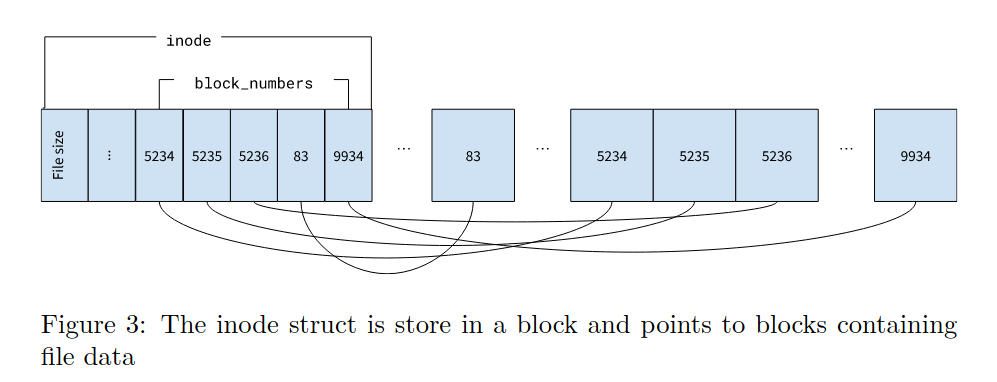

Files often contain data that spans multiple blocks. It uses inode to specify a file.

Max file size (for ext4)

- See

cat /etc/mke2fs.conf - Max file size depends on the block address mapping for

inodes. Direct, Indirect Block Offset, Double Indirect Block Offset, Triple Indirect Block Offset etc. See 4. Dynamic Structures — The Linux Kernel documentation

λ sudo tune2fs -l /dev/sda3 | rg -i "Block|inodes" # trimmed results, in bytes

Inode count: 28966912

Block count: 115838208

Block size: 4096

Inode size: 256

# (115838208 * 4096)/(10^9) = 474GB (my SSD size)- Max file size and Max file system/volume size are different. See What are the file and file system size limitations

- ext4 max block count : 2^32 => (2^32 * 4096)/(10^9) = 16TiB (Max file size)

- The

64bitflag allows blocks greater than 2^32 - Smallest possible blocksize for ext4 is 1024 bytes.

inode table size

bytes-per-inodeis the same asinode_ratio. This is a config option, not a property of the partition.

# inode_count = (blocks_count * blocksize) / inode_ratio

# inode_count = (partition_size_in_bytes) / inode_ratio

# inode_table_size = inode_count * inode_size- As a general rule of thumb the

inode_ratioshould not be smaller than theblocksizebecause you cannot (easily) store more than one file in one block.

Directory layer

- Unix directories are lists of association structures, each of which contains one filename and one inode number.

dentry

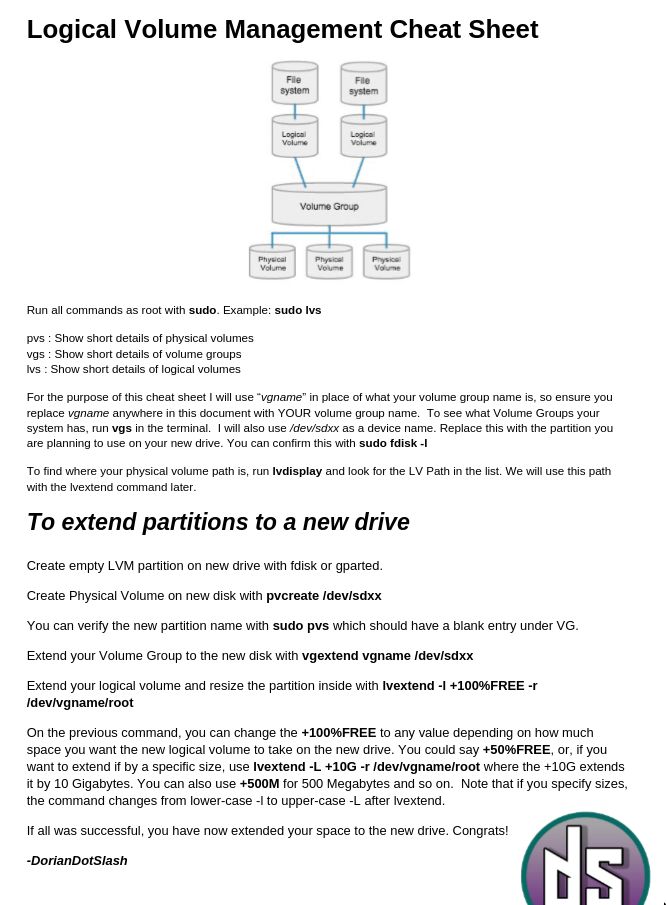

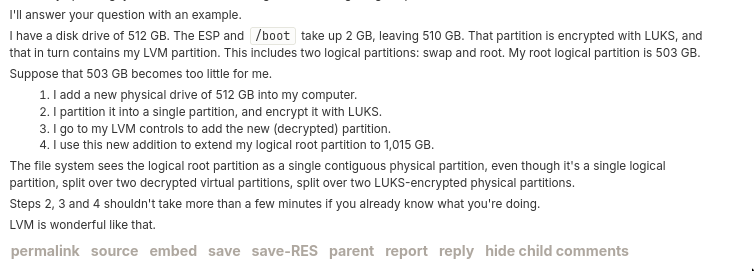

LVM (Logical Volume Manager)

See LVM - ArchWiki

See LVM - ArchWiki

- A layer above physical partitions that allows multiple partitions to appear as one.

- Grow a filesystem by adding physical space

- Physical disk like as disk or partition to be used with lvm

- LVM is useful if you want to use LUKS to encrypt your root, swap and other partitions in one encrypted volume.

- It sort of is an alternative(less featured) to ZFS and btrfs. In was it’s just a volume manager.

What’s the usual blueprint like?

esp(/boot/efi)andboot(/boot)are separatephysical partitions, not placed within LVM, because Grub has to access them at boot time.

Random notes

- Install linux distro on LVM partition

- Allows you to continue expanding the partition by adding disk on the fly

- It’s similar to RAID in a way that it gives an unified view of the underlying disks but doesn’t give redudancy and other fancy things that RAID gives you

Uses

Personal use

Practices of using LVM in the Cloud

- My verdict: Don’t do LVM in the cloud unless you absolutely have a certain usecase

- We can have multiple EBS disk mounted at diff mountpoints and our applications can make use of it. So not always the case that if multiple disks you need LVM etc.

- People have different needs and people do run ZFS/btrfs/LVM on top of Cloud volumes like AWS EBS. See AWS for more info around EBS. But usually if you just have one disk, or even multiple disk and you’re fine they being multiple disks you don’t need LVM.

- LVM also has snapshotting feature, but we already have snapshotting at cloud vendor volume level so this becomes redundant

- When you’re running VMs in the cloud, we can attach volumes. These volume allow themselves to be modified. Then you need to resize the partition and filesystem. From what I see, if it’s only one volume disk that you’re using, the steps needed are more or less the same with and without LVM.

- If you’er using multiple disks in the cloud however for some reason, LVM can help. But Volumes can grow pretty big so its unlikely you’d need to add another disk, unless there’s specific io requirements etc.

- There are other clever uses of LVM on the cloud

Related commands (TODO: Move these to plumber manual later)

- lsblk : Attached disks

- cat /etc/fstab : Mounts on boot

- df -h : Disk free on mounted stuff

- file -s /dev/xvdf : Determine file system

- fdisk -l : List all partitions

- lvm

- lvm pvdisplay

- pvs : Show short details of physical volumes

- vgs : Show short details of volume groups

- lvs : Show short details of logical volumes

Disk usage patterns

Disk usage patterns in cloud vm v/s Bare metal

How LVM becomes redundant in cloud VMs

- Instead of adding one or a few big disks and partitioning them in the VM(as we do in bare metal), we add each potential volume as an individual disk containing at most one partition.

- When you need to extend space, you increase the virtual disk in the virtualization environment, and then grow a partition and FS in a VM. This is now your LVM(the idea of it is being executed by the vendor/platform so we don’t really need to do it inside our vm).

What disks do we need in cloud VMs

- In most cases you will need a root FS and data FS, e.g. two virtual disks, and chances are the root FS disk of ~30 GB will never need to be resized.

- Databases often suggest using separate storage for write ahead logs; that will require addition of a dedicated virtual disk anyway, so to place it onto separate storage in the virtualization environment.

RAID

What

- with raid you store in a way that if a drive fails, you lose no data. (in particular types of raids)

- raid no substiutes for data.

Resources

Links

- Warner’s Random Hacking Blog: Old-school Disk Partitioning

- USB Mass Storage and USB-Attached SCSI… are both SCSI

- Data Storage on Unix

- Continuous reinvention: A brief history of block storage at AWS | All Things Distributed

- A brief introduction to SCSI

Disk encryption links

- Disk Encryption in a Linux Environment

- Speeding up Linux disk encryption

- Storage functionality - Wikibooks, open books for an open world

- Data-at-rest encryption - ArchWiki

- Arch Linux Full-Disk Encryption Installation Guide [Encrypted Boot, UEFI, NVMe, Evil Maid] · GitHub

- Opal Storage Specification - Wikipedia

- Reddit - Dive into anything

- Reddit - Dive into anything

- Ask HN: What Do You Use for Linux Full Disk Crypto? | Hacker News

- The Ultimate Guide to Using Data Encryption on Linux | LinuxSecurit…

- Reddit - Dive into anything

- Ask HN: How do you encrypt your laptops? | Hacker News