tags : Security, PKI, TLS, Encryption, Hashing

FAQ

What is a construction?

- A way of combining basic building blocks, such as encryption algorithms, hash functions, and protocols, to create a higher-level cryptographic scheme or system.

- Examples

TFAQ are .pem files?

Lingo

| Term | Description | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| PRF | pseudorandom function | HMAC |

| AEAD | It’s a construction(see Encryption), Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data | Encryption |

| KDF | Key Derivation Function | Hashing |

| Key committing | See this and this, w this, multiple keys can be considered valid by the authentication mechanism | Encryption |

| Doesn’t really de-crypt but allows doing an eventual binary search on the key | ||

| Doesn’t affect at rest data | ||

| Can be avoided by key commitment and better collision resistance | ||

| nonce | “number used once”, often a random or pseudo-random (bigger the nounce the better) | Hashing, PKI |

ECC | elliptic-curve cryptography | Cryptography |

Curve25519 | an elliptic curve used in elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) | PKI |

ECDH | Key exchange/agreement method (goal: generate a symmetric key) (basically ECC DH) | PKI |

EdDSA | digital signature scheme (But this is NOT simply ECC DSA) | PKI, SSH |

X25519 | Key exchange method implementation, ECDH over Curve25519 | PKI |

Ed25519 | Digital signature scheme implementation, (EdDSA) over Curve25519 | SSH, PKI, TLS |

HMAC | HMAC is a particular standard, not any hash-based MAC. Use of Blake3 offer similar features | HMAC |

Salsa20/ChaCha20 | Stream cipher, uses a 64-bit nonce and a 64-bit counter. | Cipher |

XSalsa20/XChaCha20 | 192-bit nonce and a 64-bit counter. | Cipher |

Poly1305 | Supposed to be used as one-time MAC | HMAC |

ChaCha20-Poly1305 | AEAD encryption algorithm, makes Encrypt-Then-MAC construction easier, faster than AES-GCM, SSH uses it | Encryption, SSH |

XChaCha20+Blake3 | Some construction by some person on the internets | Cipher |

age | See this and this | Encryption |

Blake3 | Secure cryptographic hashing hash function (FAST), can be alternative to HMAC | Hashing, HMAC |

SHA-2 | Secure cryptographic hashing hash function (includes SHA-256 and SHA-512) | Hashing |

SHA-3 | It walked so that Blake family could run or something like that | Hashing |

xxh3 | fast non-cryptographic hash function, alternative to md5 | Hashing |

Argon2 | Password hashing algorithm based on KDF | Hashing |

PAKE | ||

OPAQUE |

Passwords

Password Auth

See Authentication

Hashing passwords

This is about storing passwords “at-rest” for authentication.

- See Hashing (Password Hashing section)

- See Password Storage - OWASP Cheat Sheet Series

- See Aaron Toponce : Let’s Talk Password Hashing

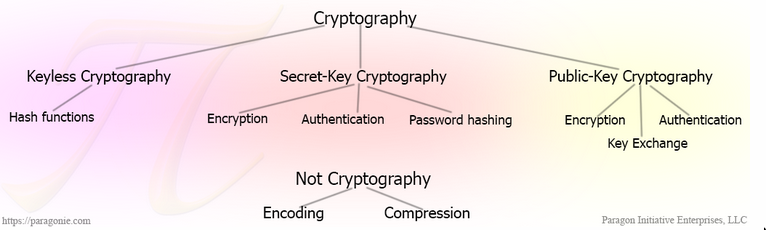

- See You Wouldn’t Base64 a Password - Cryptography Decoded - Paragon Initiative Enterprises Blog

Among these Algorithms, Argon2, scrypt, bcrypt, PBKDF2; prefer argon2.

| Strategies | Description | Basic attack | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple cryptographic hashing | Just hash the password and store it | Just get the password and launch a rainbow table attack | BAD |

| HMAC hashing (i.e keyed hashing) | Simple cryptographic hashing + Secret key | Once they get the secret key, brute-force similar to simple hashing | BAD |

| KDF(Eg. ARGON2) | specifically made for password hashing | Which password hashing you’re using is no longer a secret, algo is smart enough | GOOD |

-

Salting

modern hashing algorithms such as Argon2id, bcrypt, and PBKDF2 automatically salt the passwords, so no additional steps are required when using them.

- Different salts will result in different hashes even if the passwords are the same.

- Salt is added per user

-

Prepping

- This is a custom strategy you can apply to make the hash harder to crack

- The pepper is shared between stored passwords, rather than being unique like a salt.

- Eg. using HMAC to the generated password hash, in this case if someone gets a sql_dump, the hashes they get are not the password hashes but the re-hashes, unless they have hmac they won’t benifit

-

Don’t encrypt passwords!

passwords should be hashed, NOT encrypted.

- Hashing is the most appropriate approach for password validation

- hashing is 1-way, in-contrast Encryption is 2-way hence more dangerous. So even if attacker gets the hashed value, no dice.

- Only time you’d want to encrypt password would be to do things like keep 3rd party user secret keys securely, but i’ve seen ppl just saving them as text in db lol.

PAKE

With password based hashing, the server at the end at all times sees the actual password and does the hashing etc. when you use PAKE(has various implementation, SRP and OPAQUE one of them), then password basically never leaves the client and is hashed in client etc. Currently I don’t need this yet.

-

Basics

Password-authenticated key agreement - Wikipedia

To explain, there are two topics:

For the password KDF, you should use something better than PBKDF2 like Argon2. Also use at least the current minimum safe settings. Note these will likely increase soon with the RTX 50 series release.

This you should understand: don’t use PBKDF2 if you don’t have to. It’s not state of the art at all and too weak for today’s use. Use Argon2 instead: same goal, same use, but built to resist modern attacks. If you can’t use anything but PBKDF2 then you must not use the default parameters which are almost certainly too weak. The link by /u/Sc00bz

looks good and tells you what parameter to use PBKDF2 with to get reasonnable security.

Now the next paragraphs: /u/Sc00bz

is proposing that you use a PAKE rather than standard password hashing. So what’s that?

In general, a PAKE (Password-Authenticated Key Exchange) is a way for a client and a server to share a secret if and only if they both know a common different secret. In practice it’s a way for you to authenticate a user with a password without sending the password to the server for authentication. There isn’t just one PAKE algorithm, but several (SRP and OPAQUE in particular).

The common way to do password authentication is to store a hash of the password (provided on registration) on the server side. Then when a client wants to connect, they send the password, the server hashes it, and if it matches the stored hash they provide the client with a temporary secret (a session token in a cookie for example). There is one weakness here if the channel on which the password is sent isn’t trusted : someone may intercept and reuse the password. Even if you use TLS (as you should) it means trusting the whole certificate business (are users taking certificate errors seriously? Are these certificates really only delivered to legitimate domain owners?) as well as the server itself (if you register with a email address and a password, what’s to stop the server from trying these credentials on that mailbox? Do you really trust the server to deal with that plaintext password carefully?).

Authentication with a PAKE is different. For the user, it’s transparent: you still provide a password at registration and provide that password later to authenticate to the service. But the password never leaves the client side: the server never sees the password. Instead the client provides, at registration, what’s essentially a hash of the password and the server stores it alongside a salt. The specifics are more complex, but the principle stands: through a specific protocol, the client never sends their raw password to the server, and servers never have to store passwords, but when authentication is needed they’re able to provide the password on one side and the salt on the other to generate a random number (key) on each side. If the right password was provided for the right salt, they both generated the same key, and the client now has a shared temporary secret with the server. The only thing left is for the client to prove to the server that they have, indeed, the same key, which proves that they knew the password in the first place (for example, the server encrypts a random number with that key, and if the client is able to decrypt it it means they have the same key, which means they have the right password). Someone intercepting the communication cannot build the correct secret from looking at messages only.

What does it solve? As a user you don’t have to trust that the server deals with your password as it should: you’re never sending them your password. Also you no longer have to care about someone intercepting the authentication to get the password. As an implementer, it seems that it removes the question of how to store passwords since you don’t store a password.

What doesn’t it solve? Quite a lot actually. PAKEs are cool, but there are still tons of things you must be careful about.

What the server stores is akin to a password hash. It’s not as simple as a sha256 or even bcrypt hash for example, but it’s still something that you can crack. This means that weak passwords are still at risk if the server is compromised: cracking is possible. How hard is it to crack compared to argon2 or bcrypt? I don’t know, it depends on the specific PAKE used and I’ve never seen a good comparison. At this point I see no reason to believe that they’d be as cracking resistant as argon2 for example: it’s possible they are but in the case of SRP at least it’s clearly not designed with that in mind and I’ve yet to see a study. This also means that you haven’t really solved the need to trust the server: the server itself may attempt to crack your passwords for their own use: they have access to the DB and plenty of time. This means that using strong, unique passwords is still required of the user.

Do they solve the MITM issue? Partly. An attacker cannot have the password, sure, but the password is generally not what you’re really trying to protect. If you use a PAKE to authenticate your users but don’t use it to build a separate encrypted channel for the remainder of the communications then you’re still relying on TLS for the security (see edit below). You may have authenticated in a better way, but if you send cookie-authenticated messages in a TLS channel and that channel is compromised then the attacker can steal that cookie and perform their own requests. Also, not all PAKEs are created equal: SRP is a good example of a weak PAKE which sends the salt used by the server to the client during authentication. This allows a precomputation attack by someone intercepting traffic: they may not know the password, but with the salt they can built a dictionnary of possible hashes so that, if they ever get access to the server, they can crack the password very quickly by directly comparing salted hashes. In short, it doesn’t make the attack possible, but if the attack is ever possible it makes it more potent. OPAQUE doesn’t have that issue.

All in all, if you use strong unique passwords and use PAKE as not just an authentication mechanism but a key exchange to build an authenticated channel (possibly within the original TLS channel) then you have a good improvement over the classical password-hash-based architecture. Otherwise, while I find PAKEs very interesting, I don’t think they’re worth the effort in the context of password-based web authentication. But that’s just my opinion.

With that said, what /u/Sc00bz

is saying is that using a PAKE would relieve you from many difficult design decisions which would make your system more secure, more easily. They then proceed to explain that you should use SRP6a for that because while it’s clearly not the best on paper it’s the easiest to deploy and they then go into details of several designs. Personally I think that SRP is really badly designed and the mere fact that we’re already at version 6 shows a whac-a-mole dynamic that demonstrates this bad design. If you want to try your hands at a PAKE I think OPAQUE is where it’s at today, but really I think that the promise of “easy security with less efforts and no hard decision” is a gross oversimplification.

EDIT: I talk about a channel within a TLS channel for a web application, but I somehow just realized that for a website to know about establishing such a channel they’d have to do it in JavaScript, which means they need to download the corresponding JS from the website…over TLS. So you can scrap that idea: if you don’t trust TLS you can’t trust it more with a PAKE.

- Augmented PAKE

-

Links

- https://www.reddit.com/r/crypto/comments/1ffnkb0/password_hashing_and_file_encryption_from_same_key/

- User authentication with passwords, What’s SRP?

- https://blog.cryptographyengineering.com/2018/10/19/lets-talk-about-pake/

- https://github.com/zksecurity/zkBank/tree/main

- https://www.reddit.com/r/crypto/comments/16fntuc/crosspass_a_mobile_app_to_exchange_passwords_and/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/programming/comments/q5qgp5/opaque_the_best_passwords_never_leave_your_device/

- https://tobtu.com/blog/2021/10/srp-is-now-deprecated/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/1Password/comments/10druxo/secure_remote_password_questions/

- https://blog.1password.com/developers-how-we-use-srp-and-you-can-too/

- https://github.com/ory/kratos/issues/1246

- https://blog.cloudflare.com/opaque-oblivious-passwords/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/crypto/comments/vybjaz/could_opaque_be_postquantum_resistant/

password-based challenge

SCRAM

The beauty of SCRAM is that both authenticating parties (in this case, your client/application and PostgreSQL) can both verify that each party knows a secret without ever exchanging the secret. In this case, the secret is a PostgreSQL password!

- How to SCRAM in Postgres with pgBouncer | Crunchy Data Blog

- Get Your Insecure PostgreSQL Passwords to SCRAM | PPT

- https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc5802

-

Basics

- The basis of SCRAM is that both a client and a server

- will send each other a series of

cryptographic proofsdemonstrating that they know the secret (i.e. the password). - Needed keys

- “Client Key”

- “Server Key” (Server needs to know)

- “Stored Key” (Server needs to know)

- will send each other a series of

-

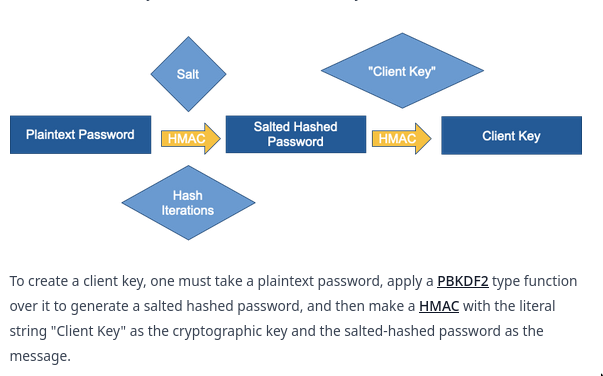

Client key

-

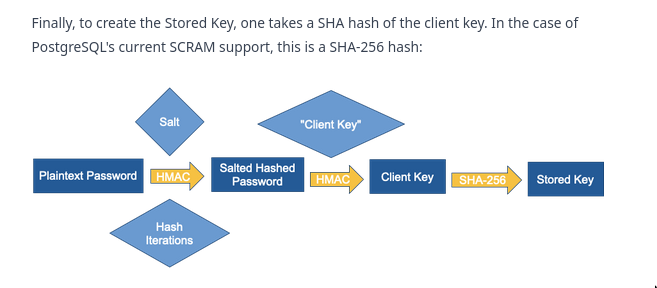

Stored key (Derived from Client key)

-

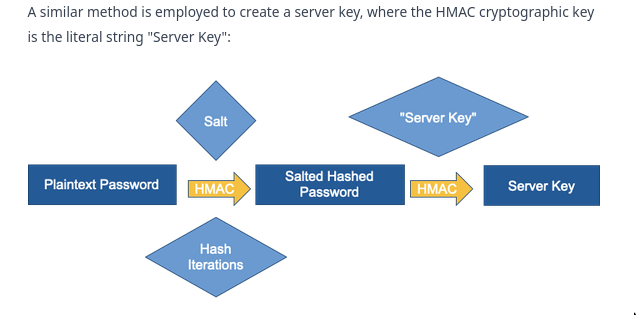

Server key

- The basis of SCRAM is that both a client and a server

-

Flow

You connect to you PG server using normal username and pass only, all this mumbo/jumbo is what your postgrest client library will handle. SCRAM is well supported.

-

Client

Sends the server a

"client proof"client proof = client key XOR client signatureclient signature = HMAC(one-time info of signing key) + stored keystored key = sha256(client key)

-

Server

Derives the

client keyfromclient proofand verifies if it OK by taking aSHA-256(client key)and comparing it againststored keyi.e Server uses the

stored keyfor two different usecases- Since server has

stored key, and it only sends the one time info- It can generate the

client signature

- It can generate the

- So once it gets the

client prooffrom a client,client key = client_signature XOR client_proof

- Since server has

-

Flow when we’re using PGBouncer

- How to SCRAM in Postgres with pgBouncer | Crunchy Data Blog

- The above nicely describes how 2 parties are talking, when we have a 3rd party(pgbouncer) things get a little bit different

client key = salt(password), wheresaltis sent by the server at initial requeststored key = sha256(client key)- Flow

- In this flow, we’re trusting the pgbouncer instance.

- client sends

client proofto pgbouncer - pgbouncer extracts the

client keyjust liek pg would - pgbouncer now generates a new

client proofwhere pgbouncer is now the actual client and sends the newclient proofto pg

-

-

Comparison with md5(See Hashing) for PostgreSQL

'md5' || md5(password + username)- If you have access to someone’s

- username / password combination

- or their PostgreSQL MD5-styled hash

- You could log into any PostgreSQL cluster where the user has the same username / password.

- The md5 has a challenge/response thing but the password itself is not salted!

-

Attacks

Replay attacks: These are prevented by md5 because there is a challenge/response component, so the md5 hash which is stored is not what is sent across the wire.- But someone with enough skills can still try figuring things out.

Gaining dump of the at-rest-hash: If an attacker somehow gains access to the at-rest-hash, then they can figure out the actual password.- Using something like SCRAM prevents this.

- If you have access to someone’s

Other topics

Forward secrecy

- If you lose your key to an attacker today

- They still can’t go back and read yesterday’s messages

- They had to be there with the key yesterday to read them

- Layman implementation

- 2 secret keys: a short term session key and a longer-term trusted key.

- The session key is ephemeral (usually the product of a DH exchange)

- The trusted key signs the session key.

- See Forward Secrecy {The Call of the Open Sidewalk}

Cipher

See Cipher

Things I keep hearing about

- AES-CTR, HMAC-SHA2

- XChaPoly

- XChaCha

- Blake

- Macaroons

- Biscuit

Tools

- https://github.com/zxcvbn-ts/zxcvbn (strength estimator)